Editor’s note: Mr Stan Kaslusky is a member of “The Gambrinus Beer Stein Collectors Club, of Va., Md., and DC.” Now a Virginia resident he has an eclectic collection of steins picked up in his travels throughout the USA over the years.

[This page was originally published in the June 2103 issue of “Prosit” (the SCI magazine) and is reprinted by permission from the author.]

The picture ▲is of a Westerwald Steinzeug stein that sits proudly in my den here in the Blue Ridge of Virginia. I recently purchased it from an antique dealer who shares (SWEARS?) that he found it in an old barn in Lancaster County Pennsylvania.

My information courtesy of the SCI Library tells me that this stein is circa 1750’s and comes from the region of the Rhine Valley often referred to as the Palatinate. The region extended from Switzerland up through present -day Germany and sometimes France (depending on which Prince had won the last scrimmage). Twice as tall as it is wide this stein shows its age beautifully with its light gray clay form and the telltale signs of having been turned on a potter’s wheel, scribed with a design of a waterfowl and painted with cobalt oxide dyes. The stein was then placed in a kiln up to 2200 degrees and salt was introduced into the kiln creating the salt glaze. The bottom shows the result of cutting the stein off the wheel with a knife and then smoothing it with the potter’s thumb.

Sources tell how potters from Holland fled the religious persecutions when Philip II in 1556 inherited the throne of Spain along with several nations including the Netherlands and settled in the Rhine valley. An industry of earthenware developed and gave the region the name “Krannenbackerland” or Jug Baker’s Land.

So how was it possible that this stein came from the Palatinate to Pennsylvania and now to Virginia? Wouldn’t it be wonderful if our steins could tell of their adventures? Of course we can never know for sure but the possible path of this stein tells a history that speaks to the core of our national spirit and the courageous people who ventured here.

Reflecting on where I came from, my Mother’s family came from Pennsylvania “Dutch” stock. Lots of meat and mashed potatoes; green bean salad; noodles; sauerkraut,; in short, comfort food. “Where did our ancestors come from”, I would ask? “Pennsylvania of course”, would come the reply. As I’ve reached retirement and finally found some discretionary time I began to study further the provenance of these people and their emigration from Germany.

Many colonial settlers in Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and Carolina came from the Palatinate; up and down the Rhine valley. From 1683 to 1776, 120,000 Germans arrived in the colonies. Genealogists can trace these families through the records of the Pennsylvania State Archives listing the many ships that arrived in the port of Philadelphia during this period.

To understand the great Palatinate migration one must go back to the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century, the resulting 30 Years War 1618-1648, religious unrest, and the Peace of Westphalia that intended to bring it to a close.

The Peace established that three religions would be recognized in the area and that princes of each locality could determine which religion would be practiced in their domain. The Roman Catholic Church continued to be accepted by the Holy Roman Empire and France. The treaty however allowed religious freedom for the churches adhering to the Augsburg Confession. This included the Lutherans and the Reformed Church, which were followers of the Swiss reformer John Calvin. An ongoing problem in the region was that with the death of a prince or with the rampage of a neighboring lord the religious mandate might be changed and the non-adherents not willing to convert would be persecuted. Religious fervor swept the region leading to new forms of worship coming out of the freethinking of the reformation. Some were tolerated; many were not. Those calling for adult “believer’s” baptism were particularly singled out.

A distant Grandfather of mine, Wilhelmus Knepper, in 1708 broke from his Reformed church in Solingen and joined with a group of “Dunkers” by getting baptized in the Eder River. For this act of defiance against the practice of infant baptism he and his young friends were put on trial and sentenced to life in prison. After some years of hard labor, constructing the castle in Dusseldorf, a protestant benefactor from the Netherlands paid for his release on condition that he emigrate to America. In 1720 he arrived in Philadelphia to begin a new life and helped to form a Protestant denomination to be known as the Church of the Brethren.

Other distant grandfathers from Switzerland and Alsace, were no doubt lured by the opportunities in the new world to purchase their own land, practice their religion, and an opportunity to practice a trade of their choosing. Hardships in the Palatinate in the 1700’s have been documented describing the area being ravaged by years of war. Taxes were issued to pay for these military exploits and the new appetites for lavish surroundings brought on by the splendor of Versailles that had bedazzled the many petty rulers of Germany. As if that was not enough hardship, severe temperatures created a mini ice age in Europe at that time and the harsh winters resulted in crop failures with loss of orchards and vineyards.

Real Estate promoters from England went to the Palatinate in 1705 and began advertising the opportunities that were available in the New World. Queen Anne of England took a special interest in the plight of Protestants and sent promoters to recruit families to move to the new world to work the plantations. William Penn went to the Palatinate to promote his new lands in Pennsylvania where religious tolerance and opportunities were promised for all. In some cases passages to America would be provided or purchased to emigrate and work the new lands. In other cases indentures would be signed to pay for transport. One Granddad, Christian Riddlesberger signed an indenture that eventually led to parcels of land in Carolina and Virginia. Many came to Pennsylvania, first to Germantown, then to Lancaster and then westward to the frontier of western Pennsylvania, Cumberland county and todays Franklin county. So many Germans populated Pennsylvania that the assembly considered, unsuccessfully, a bill making German the official language of the colony.

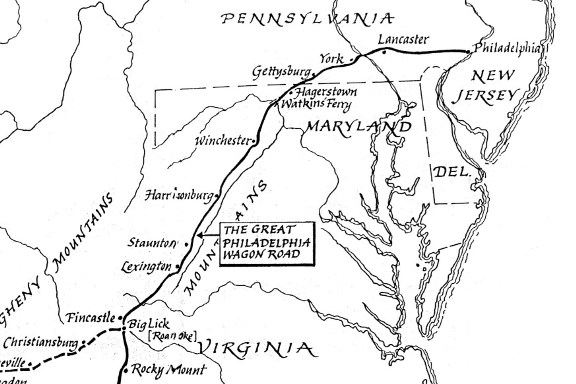

German immigrants became familiar with the Great Wagon Road. The road was an Indian trail at first and then a road enhanced by the proprietors of Pennsylvania which took settlers from Philadelphia to what was to become Waynesboro and Chambersburg. The Wagon road then headed south through the Appalachians through Maryland and Virginia. Settlers traveled the road looking for the promise of cheaper lands, and following their fellow congregants, spread churches and towns along the road. Today the Great Wagon road exists in modern form as route US 11 and Interstate 81. These German settlers, in spite of their often-pacifistic beliefs supplied many volunteers for the Revolutionary War.

The story of the ethnic groups that settled the Appalachian region and neighboring valleys is vividly told at the Frontier Culture Museum in Staunton Virginia. The Museum is an outdoor reconstruction of authentic farms from the areas in Europe where settlers came from in the 1700-1800’s. The museum gives a hands-on feel for the origins of these courageous colonials. Visiting the museum one sees an authentic English farm, an Irish Farm, an African Village and a beautiful farm from the German Palatinate.

The German farmhouse and barn were moved from the Rhine valley in Germany and reconstructed in Staunton. Guides dressed in period clothing and cultural exhibits tell the stories of the early settlers, and the lands that they left in the Old World. The German farmhouse has a small yet appropriate display of Beer steins that would have been in a Palatinate home.

Whatever their journey these objects provide an opportunity to study their origins and the times and people who possessed them. They continue to enrich our imagination and education beyond their simple function…that of enjoying a great beer.

Detail of the above steins ▲.

Editor’s note: While these stein do represent older Westerwald pieces, they are in fact all modern renditions of the older ones. These three were made by Gerz [?] in Germany and sold as limited editions back in the 1980’s and 90’s, I think. This is not an unusual practice of having reproductions showing to the public, as 99.59% of the visitors couldn’t tell the difference , and the museum doesn’t have to lay out lots of cash for the display. In this case it would probably cost them close to $2000.00 to buy the authentic steins.

Sources –

-Early Palatine Emigration, Walter Allen Knittle, PHD, Philadelphia, 1937

-Westerwald Steinzeug 1600-1914, John McGregor

-The Origin of the Schwarzenau Brethren – Marcus Meier

-The Historical Sketch of Franklin County Pennsylvania – I.H.Mcauley

-The Riddlesbergers, Arthur R. Seder, Jr.

-The Beer Stein Book, Gary Kirsner

[END – SOK – 07 – R5 ]

WISH TO CONTACT ME ? =

“It’s hard to make a comeback when you haven’t been anywhere!”

“It’s hard to make a comeback when you haven’t been anywhere!”

Leave a Reply